First written in English, “The Andalusian Zorro Song” was translated by the author into French and performed with a team of nine actors and musicians in Saint-Jacques-de-la-Lande (Rennes), Lille and Bagnolet (Paris) in 1999-2001. (additional notes in English at end of page)

Appelons ceci une pièce avec des chansons – une sorte de songspiel dans la tradition Brecht/Weill, bien qu’il s’agisse plus du spiel que du song. En même temps, comme l’indique le titre, l’idée est celle d’une pièce qui soit elle-même comme une longue chanson avec ses thèmes récurrents, ses refrains et ses digressions.

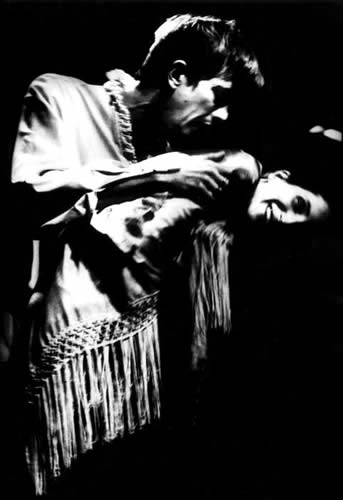

Le tonalité est celle du contraste : le bien contre le mal, bien entendu, puisqu’il s’agit de la notion du Zorro. Puis, le ridicule du pathos narcissique face à l’inéluctable marche de l’histoire. Ou encore, la libération par le sexe face à la libération par la lutte. Le fond noir est ponctué par des reflets de peau, des éclairs d’armes et l’apparition pénétrante du soleil andalou. Du dîner de famille en plein désintégration au gouffre moite et salvateur de l’amant/abri et de l’alcool, il est clair : Zorro va arriver, mais est-ce pour le mieux ?

Theo Hakola

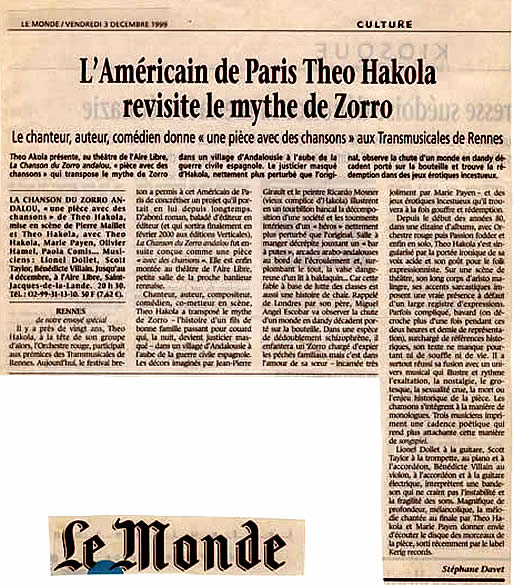

“Chanteur, auteur, compositeur, comédien, co-metteur en scène, Theo Hakola à transposé le mythe de Zorro – l’histoire d’un fils de bonne famille passant pour un couard qui, la nuit, devient justicier masqué – dans un village d’Andalousie à l’aube de la guerre civile espagnole. Rappelé de Londres par son père, Miguel Angel Escobar va observer la chute d’un monde en dandy décadent porté sur la bouteille. Dans une espèce de dédoublement schizophrène, il enfantera un Zorro chargé d’expier les péchés familiaux ( … ) Surchargé de références historiques, son texte ne manque pourtant ni de souffle ni de vie. Il a surtout réussi sa fusion avec un univers musical qui illustre et rythme l’exaltation, la nostalgie, le grotesque, la sexualité crue, la mort ou l’enjeu historique de la pièce. Les chansons s’intègrent à la manière de monologues. Trois musiciens impriment une cadence poétique qui rend plus attachante cette manière de songspiel.”

Le Monde 1-12-99

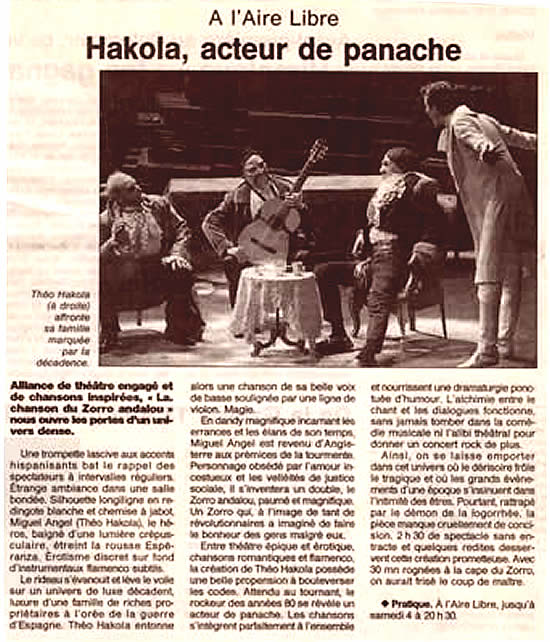

“Entre théâtre épique et érotique, chansons romantiques et flamenco, la création de Theo Hakola possède une belle propension à bouleverser les codes. Attendu au tournant, le rocker des années 80 se révèle un acteur de panache. Les chansons s’intègrent parfaitement à l’ensemble et nourrissent une dramaturgie ponctuée d’humour (…) Ainsi, on se laisse emporter dans cet univers où le dérisoire frôle le tragique et où les grands événements d’une époque s’insinuent dans l’intimité des êtres.”

Ouest France 2-12-99.

Photos

Press

Presto : “La Chanson du Zorro andalou”

References

1997 – “La Chanson du Zorro andalou” – texte complet en français

1993 – “The Andalusian Zorro Song” – complete text in English

Notes

THE ANDALUSIAN ZORRO SONG

I’m calling this piece “a play with songs.” It might best be labeled a kind of song spiel, in the Brecht/Weill tradition although it’s certainly more spiel than song. In any event, the songs rarely take the place of dialogue. They emerge, seamlessly one hopes, in the form of monologue declarations, for the most part and they are as likely to be directed at the audience as not.

You probably have an idea of the basic Zorro legend. The Tyrone Power vehicle, “The Mark Of Zorro,” sets it up nicely: 18th Century Spanish California where the kindly colonial mayor of a town is being assailed by the corrupt and downright mean-spirited colonial army commander. The good man sends for his son who is still back in Spain – a promising cadet in the elite royal military academy. But much to his father’s chagrin, the young gentleman proves to be a weak-kneed embarrassment. Useless. The son’s cowardice, however, is only a masquerade behind which Zorro – the son in disguise of course – can most effectively emerge to dashingly slash his way through the bumbling bad guys, save the peons, bail out his father and, ultimately, “get the girl” when he finally reveals his true self.

My Zorro story takes place in Andalusia – in a Spain on the verge of civil war in 1936. “The Beleaguered Father,” SEÑOR ESCOBAR, is an important landowner besieged by his peasant laborers, the Republican government and anxiety over his role in the ever-brewing right-wing coup.

“The Useless Son,” MIGUEL ANGEL, has been called home from his studies in London in my story but this time his character flaws might be real. He is a frightened, pathetic drunk. As in the original, he remains ZORRO’S generator, but it now seems that the righteous masked man in black comes to life as a schizophrenic reaction of atonement for MIGUEL ANGEL’S family’s sins. ZORRO exists more as an unavoidable product of MIGUEL ANGEL’S shame than as a function of the specific exercise of his will.

It seems…

“The Girl” in my story is the wise ESPERANZA, a key presence throughout as MIGUEL ANGEL “gets her” from the beginning. In a frankly sexual relationship, she is MIGUEL ANGEL’S hiding place, when alcohol is not enough, and later, his worst pain when she can no longer stand intimacy with him. She is also MIGUEL ANGEL’S sister, though she could just as easily be a long lost second cousin: sister and brother hardly knew each other growing up.

The town is Bracera. Controlled by the ESCOBAR family for as long as anyone can remember, it, like so much else, is slipping through their hands as the democratically elected Republican government comes increasingly down on the side of social justice.

The Mexican peons – “The Noble Poor,” on whose behalf Tyrone Power’s Zorro wields his sword – become the more politically sophisticated anarcho-syndicalist peasants of my story. My ZORRO, a kind of unhappy hybrid of a wannabe Che Guevara and an atheist zealot Jerry Falwell, (not to mention Dudley Doright for the ineptitude), is more stick in the spokes than savior for these campesinos. Their leader, IGNACIO, is an “other side of the tracks” childhood friend of MIGUEL ANGEL’S who, like everyone else, now disdains the decadent señorito. In the ultimate act of self-flagellation as expiation, ZORRO will enthusiastically advocate the execution of MIGUEL ANGEL and his family.

I’d like to think that it’s funnier than it sounds here.

It’s also a bit of a soap opera/melodrama, spiraling down to that inevitable Greek tragedy finish when the long smoldering embers finally erupt in the terrible fire of the Spanish Civil War and, in Bracera as elsewhere on the peninsula, the long accumulated debts are paid in blood. Death. And we finish with the post-mortem denouement – magical realism (or clever gimmickry) as the story resolves itself in a purgatorial finale.

Theo Hakola